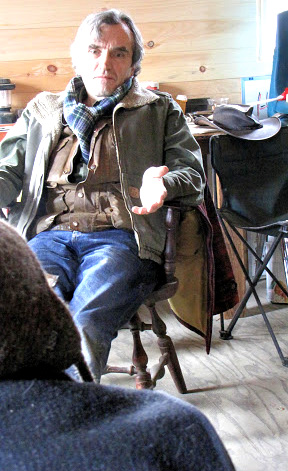

Local environmental educator and raconteur Chuck Stead remembers the days when he was just a boy in the mid-1960s and would wander the wonderland that was Torne Valley, setting small game traps. Stead, who grew up in Hillburn, NY, roamed the valley like it was his own back yard.

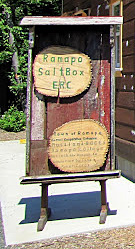

“Trapping, you’d come in at night and reset the traps,” said Stead, now a Nyack resident, discussing the history of the valley at the Ramapo Salt Box he and his students built as an environmental and educational research center. “Then I’d come in the morning to pick up my game before school.”

“Trapping, you’d come in at night and reset the traps,” said Stead, now a Nyack resident, discussing the history of the valley at the Ramapo Salt Box he and his students built as an environmental and educational research center. “Then I’d come in the morning to pick up my game before school.”

Stead recalled asking his uncle why the big tractors in the valley were digging at night.

They’re dumping paint from the Ford plant in Mahwah, he was told.

“I saw it happening and I thought they were excavating,” Stead said, remembering stories he had heard from people about night runs from the Ford auto plant in Mahwah, NJ. Roaming the valley checking on his traps, Stead noted how the tractors that worked the sand quarry would be in different places, with trenches filled in from the night before.

Much of Torne Valley at the time was owned by the Ramapo Land Company and used as both a sand quarry and dumping ground. Those were the days before federal regulation had any real oversight, when companies would land fill waste products in rural areas, just as people would regularly toss trash out of car windows, sailing it down someone else’s roadside. Then the Clean Water Act was enacted in 1972 and a sea change in behavior followed.

“I eventually poked around. The way it worked is guys would drive their trucks here with 55 gallon drums of paint in them. If you could put six barrels in the back of your truck and make them disappear in the middle of the night, you’d get a hundred dollar bill.”

“I eventually poked around. The way it worked is guys would drive their trucks here with 55 gallon drums of paint in them. If you could put six barrels in the back of your truck and make them disappear in the middle of the night, you’d get a hundred dollar bill.”

Stead said pickup trucks with tarps over the barrels would sometimes be parked around the old sand quarry area, which eventually become the Ramapo Landfill.

“I smelled the paint,” said Stead. “It was liquid then and it was strong,”

Stead memories of the valley history are so vivid because he kept detailed animal trapping and outdoor adventure notebooks that marked down the various locations where pickup trucks were dropping their toxic loads. Throughout the years of building the Saltbox house, Stead and his students revisited and marked the sites — 16 in all.

Stead memories of the valley history are so vivid because he kept detailed animal trapping and outdoor adventure notebooks that marked down the various locations where pickup trucks were dropping their toxic loads. Throughout the years of building the Saltbox house, Stead and his students revisited and marked the sites — 16 in all.

Cleaning Up Torne Valley

Now Ford Motor Co. is cleaning up the old buried paint sludge in Torne Valley along the Ramapo River. The work is visible from Orange Turnpike where it turns into Rt. 59, across the Norfolk Southern Railway tracks. The cleanup effort involves big equipment that has torn out trees and cleared land near a United Water well field, creating both a staging area to house old paint sludge and to clean up the toxic mess itself.

Phase 1 of the cleanup project, or OU1 (Operational Unit 1 in environmental mediation speak), covers a large tract of land near the Ramapo River and occupies the site where United Water pumps a good deal of Rockland’s water supply. According to Stead, the cost to Ford for the first phase is $12 million. Ford, using the engineering and management company Arcadis, has hauled out an excess 30 thousand tons of contaminated sludge and soil.

Stead said the material is being sent to a solid waste furnace that burns it down to near nothing and then contains whatever remains.

Stead said the material is being sent to a solid waste furnace that burns it down to near nothing and then contains whatever remains.

Unlike in previous related remediation efforts, including Hillburn and Ringwood, documented extensively by the Bergen County Record in its Toxic Legacy series, the Torne Valley cleanup includes complete removal of the contamination.

“I’m not trying to get him re-elected or anything but St. Lawrence [Town of Ramapo Supervisor Christopher St. Lawrence] has done this without litigation, which is why we’re going to have full remediation whereas Ringwood did not,” said Stead. “This is a guy who has taken a lot of shots but when everything’s said and done, there’s a legacy there.”

“Because he’s a good wrangler,” Stead said about Ramapo Supervisor Christopher St. Lawrence, “he’s gotten them [Ford] committed to a full remediation. Of course it’s not complete yet, so let’s see what happens.” Stead, along with St. Lawrence, will give a presentation on the Ford remediation at this year’s Ramapo River Watershed Conference on Friday, April 26, at Ramapo College. “It is a major feather in his cap. He’s been able to use this Saltbox project as leverage with Ford. It’s been wonderful.”

Stead’s Saltbox house sits like a sentinel next to the Ramapo Landfill, which opened as the town’s official landfill in 1972 and then ceased operation around 1982 for various violations and issues of contamination. The landfill site is now an official Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Superfund site, capped with greenery while the toxic contamination underneath settles. Phase 2 (OU2) of the cleanup is scheduled for the winter/spring 2014 and includes a cleanup in the wetlands and woods adjacent to the Saltbox. The phase also involves a small section along Torne Valley Road across the river from the present cleanup site.

“That’s the very first area I saw the trucks with the 55 gallon drums,” Stead said about the planned OU2 site , which is in the approximate area along the Ramapo River where Sloatsburg Elementary School 4th graders visit annually on their historical field trip around Sloatsburg.

“That’s the very first area I saw the trucks with the 55 gallon drums,” Stead said about the planned OU2 site , which is in the approximate area along the Ramapo River where Sloatsburg Elementary School 4th graders visit annually on their historical field trip around Sloatsburg.

Phase 3 would take place in 2015 at a small site in Pomona, NY.

In A Boy’s Dream

With his rebuilt Ramapo Saltbox Environmental Research Center (ERC) house planted firmly in the valley, Stead’s longview vision for the reclamation of Torne Valley as an expansive educational hub is taking shape. The Saltbox house itself represents the kind of old housing that at one time stood in Ramapo Hamlet, the old work camp along the Ramapo River for the Ramapo Iron Works founded by Jeremiah H. Pierson in the first half of the 19th century and operational from 1795-1854. The Hamlet also housed the cotton mill built in 1816 by the Pierson family, which still stands as modern warehouse space where the old bridge crosses the Ramapo River.

Under the shadow of the mountain and downhill from his old home village of Hillburn, Stead has planted his educational and spiritual flag. Just recently, the Saltbox hosted students from Professor Howard Horowitz’s Ramapo College Water Resource class, who visited the Saltbox and the new Hillburn water and sewage treatment facility. Then the group trudged into the field to see what environmental remediation looks like in the raw — paint sludge, gray and decaying in the valley wetlands while uprooted and heavy earth-moving equipment was digging up the toxic past.

Under the shadow of the mountain and downhill from his old home village of Hillburn, Stead has planted his educational and spiritual flag. Just recently, the Saltbox hosted students from Professor Howard Horowitz’s Ramapo College Water Resource class, who visited the Saltbox and the new Hillburn water and sewage treatment facility. Then the group trudged into the field to see what environmental remediation looks like in the raw — paint sludge, gray and decaying in the valley wetlands while uprooted and heavy earth-moving equipment was digging up the toxic past.

With a student lab on the second floor of the Saltbox, Stead’s students, from BOCES of Rockland to Rockland AmeriCorps and Ramapo College, continue to work on any number of projects, with support and partial funding from the Town of Ramapo’s Cultural Property Management department, headed up by Tom Sullivan.

There’s also a nice new space beside the Saltbox, cleared, leveled and awaiting an old Dutch barn purchased from the Rockland County Historical Society by the town. Ever the teacher, Stead plans a sort of barn raising, where students will continue to work with their hands and minds, while contributing to turning Torne Valley into a vibrant hub. Then after work and study, comes play. Stead envisions the barn and Saltbox as a center for cultural and community education and celebration, such as the recent Ramapo Saltbox Solstice that honored and remembered those lost in Newton, Connecticut.

There’s also a nice new space beside the Saltbox, cleared, leveled and awaiting an old Dutch barn purchased from the Rockland County Historical Society by the town. Ever the teacher, Stead plans a sort of barn raising, where students will continue to work with their hands and minds, while contributing to turning Torne Valley into a vibrant hub. Then after work and study, comes play. Stead envisions the barn and Saltbox as a center for cultural and community education and celebration, such as the recent Ramapo Saltbox Solstice that honored and remembered those lost in Newton, Connecticut.

Stead’s Antioch advisor Alesia Maltz, from Antioch School of Environmental Studies in New Hampshire, called the foothills and lands at the foot of Torne Mountain around the Saltbox “a healing place.”

“A certain symmetry envelopes the whole living classroom that is the valley,” Stead said, now a teacher in the very place he used to roam as a boy. “We talk about sustainability. But the wind here is the educator more than me.”

Photos of Chuck Stead and Ramapo College student at the Saltbox house and in the field courtesy of Geoff Welch. Also, the Welch supplied the photo of paint sludge.